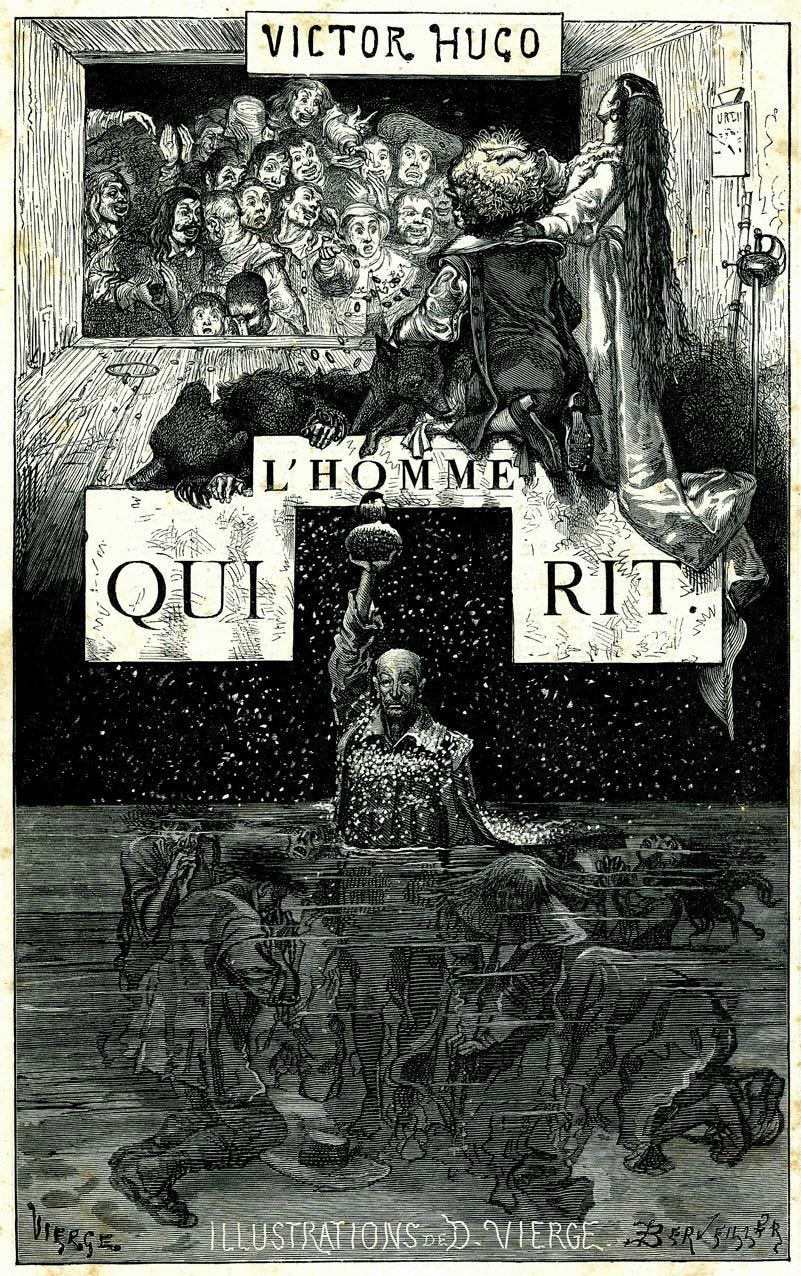

I’ve been slowly working through a little-known masterpiece by Victor Hugo, The Man Who Laughs (L’Homme qui rit, 1869). As literature, it is dazzling, though nothing Hugo has written surprises me anymore. That’s not my point here. What matters is that in this novel Hugo expressed his political views more freely than ever before – more freely even than in Les Misérables. By 1869 he had become a ferocious democrat, a liberal to his very marrow.

And this is the point: that is what genuine liberalism was and still is – the liberalism that Hugo embodied. Let me put it simply: when society changes, our perspective must change with it. Liberalism is not a fossilized set of dogmas. It has no icons, no gospels, no blind spots, no petty merchants peddling slogans. It is an ideology with one continuous, uncompromising, and by definition never fully satisfied goal: the maximization of freedom. Every kind of freedom – national, political, economic, social, spiritual – and above all, personal autonomy. The individual should be the author of her own life. That is what liberalism always was, and what it must remain. Don’t take my word for it: Madison grasped it first, and Mill gave it its philosophical framework in On Liberty (especially chapter III).

So when people reduce liberalism to something else – to repentant leftists or rightists, to rentiers who howl about paying taxes, to apologists for Trumpism, to half-educated souls whose “knowledge” comes from think tank pamphlets (Slobodian calls them “Hayek’s bastards”), to those who grow more conservative simply because they grow older, or worst of all to misanthropes whose inhumanity oozes from every opinion they express (whether on Greece, Palestine, Ukraine, refugees, migrants, LGBTQ people, minorities, the marginalized and the misérables in general) – when people identify liberalism with any of these pseudo-liberals, they are making a grave mistake. Sometimes deliberately, but often out of ignorance, and worse, out of semi-literacy.

Liberalism has specific, well-documented historical, political, ideological, epistemological – even metaphysical – roots. Before you speak about it, open a damn book. In fact, open more than one. Open many. Read them. You will not be harmed. On the contrary: the result will be that you write fewer illiterate inanities – the sort so often written by both left and right, usually by those who have skimmed the relevant literature sloppily, selectively, through filters and prejudices, instead of systematically and seriously. Yet these same people pose as gurus, when they should shut up and speak only about what they truly know (if even that).

A good place to begin is Les Misérables. Not only because it is Hugo’s best book, but because no other literary work or political treatise in history – not even On Liberty – captures so vividly the evolution of liberalism from 1815 to 1860. No other book contains a chapter like 5.4.1, which (to my advantage) no one seems to have noticed from this angle until now. No other book crystallizes the liberal experience of that century so completely, nor shows more brilliantly its foundations and the direction it must continue to take if it is to remain true to its origins and, above all, to the promise it made to humanity.

And to help you further, I’ll close with the best definition of liberalism ever given – not by a philosopher or a politician, but by an eighteen-year-old girl: Mary Godwin (later Shelley). “Liberals,” she wrote, are “all those of every nation in Europe who have a fellow feeling with the oppressed, and who cherish an unconquerable hope that the cause of liberty must at length prevail.”