The Cause of the Greeks and the Greek Constitution

How Greek revolutionaries stunned Europe with a liberal and democratic constitution in 1822

The Greek nation, which groaned under the abominable yoke of the Turks, being no longer able to support the weight of a tyranny unexampled in the annals of the world, has a at last resolved to shake it off, and proclaims today by means of its legitimate representatives assembled in national congress, in the presence of God and of men, its independence and political existence.

Given at Epidaurus, 1st of January 1822, first year of independence.

Yesterday afternoon, I arrived at the ancient city of Epidaurus after being invited by its mayor, Tasos Chronis. Although I have visited the ancient theater several times, this was only my third visit to the three towns in the area, including ancient and new Epidaurus and Ligourio. Today, I gave a lecture at Ligourio High School to students ranging from 12 to almost 18 years old. I explained to them that the modern Greek state was established in this area with the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of Epidaurus, on January 1, 1822 (old calendar).

At the time, the Revolutionary War had just begun, and the Greeks controlled only a few areas, mostly in Peloponnese, Central Greece, and the Aegean islands. Two centuries later, one may question whether the Greeks’ decision to organize themselves in such a grand way, adopting a constitution, establishing a (revolutionary) state with a parliament, a collective executive, and no less than eight ministries, was necessary.

It was needed for several reasons, one of which was to demonstrate to the European Powers that the Greeks were a Christian nation seeking independence and “rational freedom,” rather than brigands, guerillas, or an unruly tribe.

If there are any doubts about the necessity and impact of a constitutional organization in the early stages of the Revolution, let us examine what Lord Strangford, the British ambassador to Constantinople, wrote to Lord Castlereagh, the British foreign minister, on April 25, 1822:

This attempt at political organization, however rude and imperfect, promises to give a degree of consistency to the Greek cause, which it has hitherto wanted, and which will greatly increase the difficulties and disadvantages of the Porte in the present contest. I have unceasingly and most earnestly pressed this consideration on the minds of the Turkish ministers, as an argument quite conclusive in favour of an immediate accommodation with Russia.

A constitution could provide an additional benefit to the Greeks. The European liberals ranked states based on their level of constitutional organization (the ranking of states according to how liberal they are is a trait that liberals have retained well into the 21st century). On January 1, 1821, the liberal Morning Chronicle, one of Europe’s largest newspapers, published a ranking of European states based on their constitutional status. In an editorial that discussed the liberal revolutions of the late 1820 in the Iberian and the Italian peninsulas - the first insurrections in the post-Napoleonic Europe - categorized European governments in this way:

Europe, in respect to population, may be considered as pretty equally divided into Constitutional States and Republics, and States without Constitutions. The powerful Constitutional States are Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Naples; and the principal arbitrary States are, Turkey, Russia, Austria, and Prussia. The division is pretty equal in point of population; but when we speak of intelligence and civilization, it is quite another matter. The Turks are absolute barbarians; the Russians are beginning to have a glimpse of civilization; the Austrians are in the lowest scale of nations entitled to be called civilized; and the Prussians alone can be considered as on a level with the average of European population.

European liberals may have been surprised when the small Greek revolutionary state, established on Ottoman Empire lands, joined, politically, the first tier of European nations. Greece’s achievement was particularly impressive given the Ottoman Empire’s reputation for the absence of a rule of law. If these barefoot revolutionaries are indeed the descendants of the Ancient Greeks, this development would make perfect sense.

That is why many Europeans were eagerly anticipating the type of Constitution that the Greeks would adopt. In early 1822, German, French, and British newspapers featured news items on this topic.

News from the Morea is expected with some eagerness, because it is expected to contain the form of the Greek Constitution.

The demand for news about the proceedings of the Greek constitutional assembly was so high that fake news was created and published. The scenarios for Greek political organization assumed that the powerful groups in the traditional Greek Orthodox society (clergy, primates, warlords) would retain the upper hand. According to these conservative scenarios, the first Greek National Assembly

intends to publish a declaration, in which it will promise to adopt a form of Government entirely monarchical, and to accept it from the hands of the Christian Powers. The Greeks desire no other emancipation than from the insupportable yoke of the Turks.

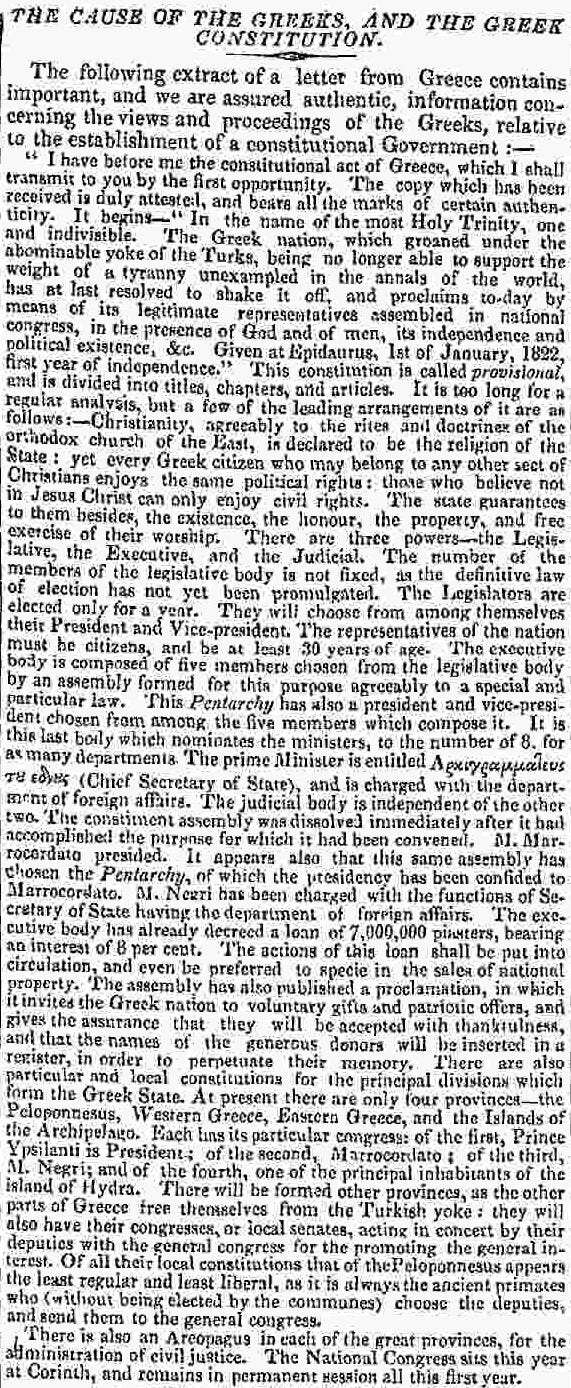

The suspense ended when the London Times published a short story on April 29, 1822, presenting the basic elements of the Greek Constitution.

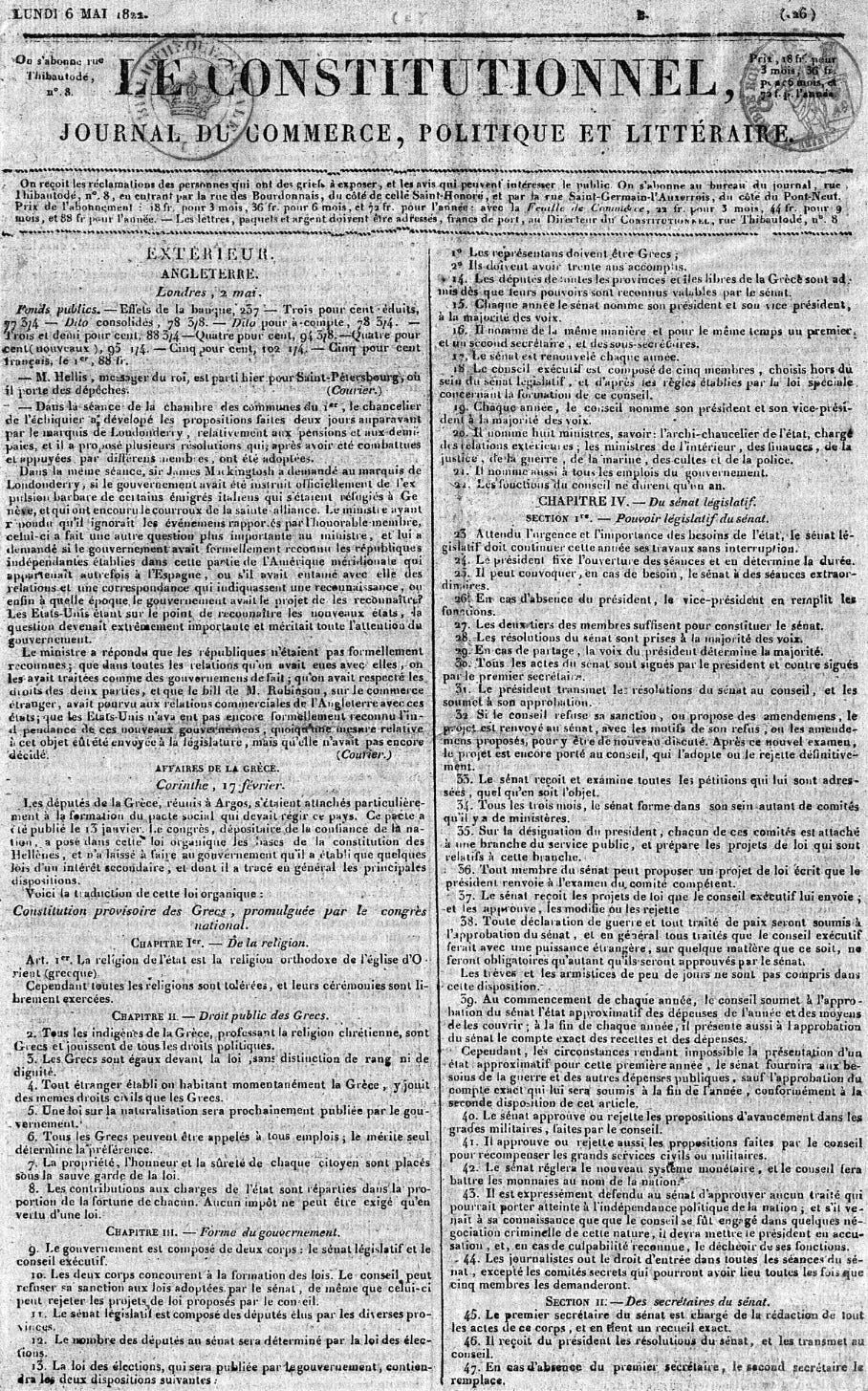

It became clear that the Greeks had established a Republic with the most democratic and liberal constitution in Europe. A week later, the newspaper with the widest circulation in the world, Le Constitutionnel, published a “French translation” of the Greek Constitution.

On May 27, London’s Sun (which is not related to Rupert Murdoch's tabloid newspaper) published an English translation of the “French translation.”

Quotation marks are used because the French text was not a translation but a preliminary draft. As I recently discovered, the Greek Constitution was originally written in French by two Greek revolutionaries and an Italian Carbonaro. All three were fluent in French and identified as liberals, with Mavrokordatos being the most moderate. His understanding of liberalism was influenced by his six-month close relationship with Mary Shelley. He did not become a radical liberal himself, but he gathered around him a circle of Greek, French and Italian radicals. The Constitution of Epidaurus resulted from the circle’s strong influence on him.

A year later, a representative of the British liberals, an Irish veteran of the Royal Navy and disciple of Jeremy Bentham, Captain Edward Blaquiere, visited Greece to assess the degree of liberalism the Greeks had achieved. His comments on the Constitution of Epidaurus (as amended in the spring of 1823 to acquire a more democratic and liberal character) were more than enthusiastic:

Adopting the most liberal institutions of Europe for their models, there was not a single clause without a precedent being previously established, either in the practice of the British Consitution or that of the United States, which the legislators of Greece consulted, as knowing to emanate from the letter and spirit of English law.

Mary Shelley was right (again) when she wrote to Maria Gisborne in early 1820:

This is the time for constitutions.

To be continued

The text you have just read is a product of my research and presents some of my original findings to a wider audience. Please respect intellectual property rights and ethical norms in research. You can read more (if you can read Greek) here and here.