The Italian “founder” of modern Greece

New evidence on Vincenzo Gallina, one of the authors of the first Greek revolutionary Constitution of 1822.

A few weeks ago, I was in Rome on a research trip. My goal was to find in the Vatican archives unknown issues of the newspaper Telegrafo Greco, published in Messolonghi (in western central Greece), in 1824 and recently discovered by my colleague Tzortzis Ikonomou. But, as is often the case, what I did not expect to find was far more important than what I was originally looking for.

In short, I found the police file of an Italian Carbonaro who will join the Greek Revolution of 1821 and will participate in the National Assembly of Epidaurus as an advisor to the Greek political leader Alexandros Mavrokordatos. The Italian patriot was the one to write the draft version (originally in French) of the first Greek revolutionary constitution, in collaboration with Mavrokordatos and the liberal intellectual Theodoros Negris. The name of this Italian Philhellene was Vincenzo Gallina.

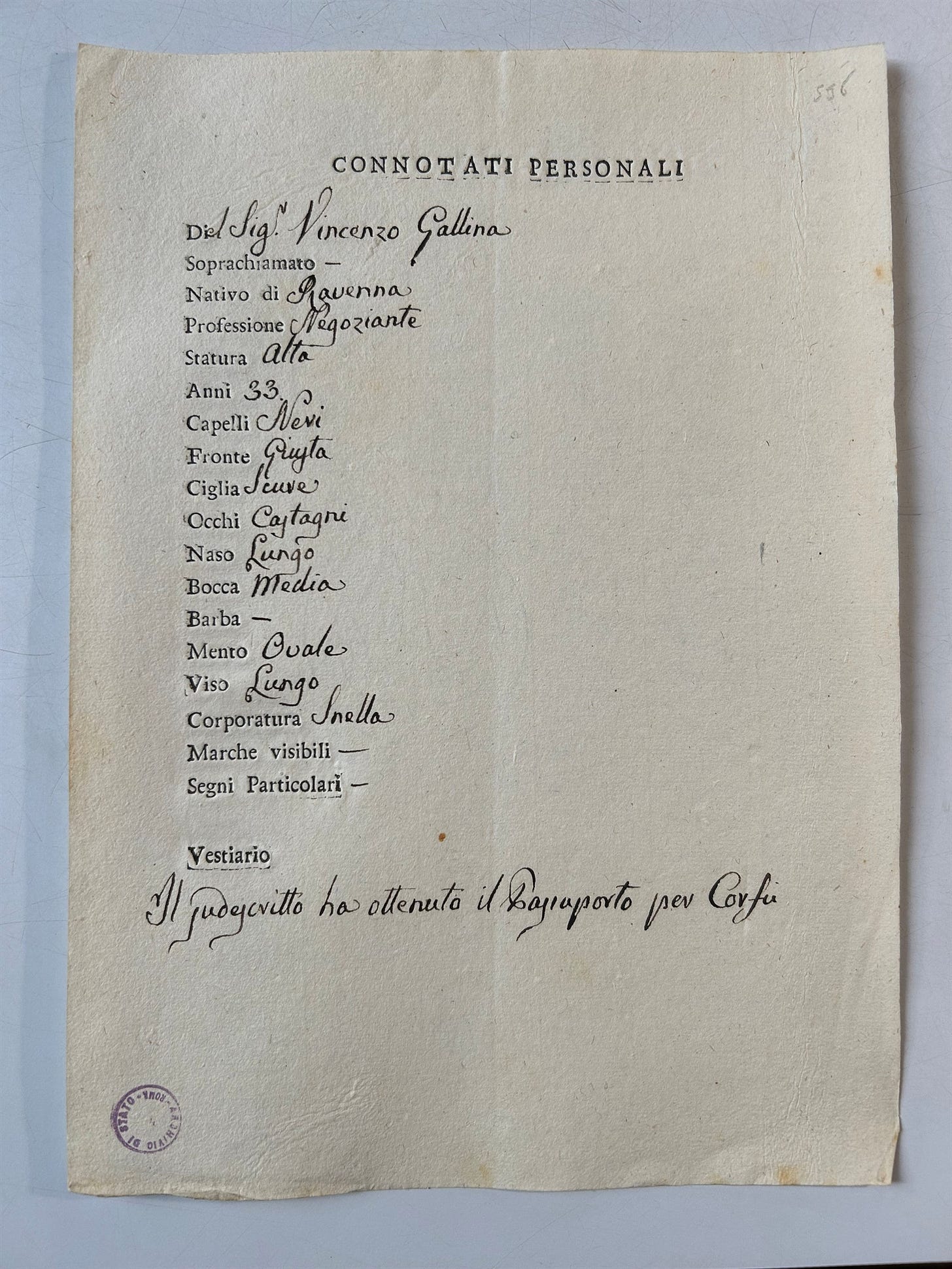

We knew very little information about Gallina, and it was not always accurate. Let me start with the most important: Gallina probably introduced himself to the Greeks as a lawyer, but in reality, he was a merchant from Ravenna, 33 years old, a liberal, a Freemason and a Carbonaro, who was exiled by the Papal States when the rebellion he organized with the collaboration of Lord Byron failed. He did not arrive in Greece on the ship that brought the Mavrokordatos entourage from Marseilles, but alone, via Ancona and Corfu.

Let’s go back to the summer of 1820. You probably know that the Greek Revolution was part of a revolutionary wave that, after starting in South America, reached Spain in January 1820, Naples in July of the same year, Portugal in August and Piedmont in March 1821. On the same day that the Greek revolutionary leader Alexander Ypsilantis crossed the Prut River in Moldavia, on the Atlantic coast, in the French city of La Rochelle, a military coup was launched against the Bourbons. All these rebellions, revolutions and coups of 1820-21 did not end well for the revolutionaries. They were violently suppressed by the Holy Alliance, and the protagonists were executed, killed in battle, or (self-)exiled. The only revolution of the period that not only succeeded but also led to the establishment of an independent nation-state was the Greek one.

A large number of Italian revolutionary patriots, Carbonari and Freemasons, as well as veterans of the Napoleonic wars, left Italy and fled to Greece. Most of them (with a few notable exceptions, such as Giuseppe Chiappe or Giuseppe Pecchio), were killed in battle (e.g. Pietro Tarella and Andrea Dania at the battle of Peta or Count Santarosa at the battle of Sphacteria), fell ill and died (Pietro Gamba) or left Greece as desperately as they had left Italy. One of the latter was Vincenzo Gallina.

Gallina was a merchant in Ravenna, he was deeply involved in Freemasonry, he was the leader of the Carbonari and the liberal bourgeois of the city. He collaborated with the young Count Pietro Gamba. Gamba was the brother of Byron’s lover, Teresa Guiccioli, and a close friend of Byron – he would accompany him to Greece and become the editor of Telegrafo Greco (the revolutionary Greek newspaper, written in Italian, and founded by Lord Byron himself). It was through Gamba that Gallina met Byron and introduced him to the conspiracy being prepared by the Carbonari of Romagna, namely Bologna, Ravenna, Cesena and other smaller towns. The revolution had just broken out in Naples, revolts were brewing in northern Italy, and in the center of the peninsula the Italian patriots could not wait to act. They wanted to seize the initiative before a fait accompli was imposed on them by their compatriots in the north and south of the peninsula.

But the Holy Alliance’s counterattack soon began. By the end of August 1820, the Austrian army was camped on the Po River, 50 miles from Ravenna, and Byron wrote to his publisher John Murray that if the Huns (i.e., the Austrians) did not cross the river, an uprising would break out, but that it was likely to break out even if the Austrians decided to cross the river and invade the Papal territories to suppress the revolution in Naples – as they eventually did. But the Carbonari of the region never moved. The leaders of the groups from the various cities were afraid. On the other hand, they did not see much enthusiasm among their compatriots, especially in Bologna, and they were also afraid of the Austrian army and the Papal police.

All the information about what happened in Ravenna at that time is now in the Archivio di Stato di Roma, which received the relevant files from the Vatican. I found there the police files of the conspirators, the exhaustive interrogations of the Austrian authorities, the file of their trial in 1825.

Gallina was the most fanatical of them all, impatient, overly optimistic, pushy. In secret meetings, he claimed that all of Ravenna was ready to revolt (“we have many hunters in the area who have guns and bullets and are all ready to revolt”). His group is called the Americani because they frequent a tavern called the “Americano” (“The Americani are ready to be the first to rise,” the secret police observe). Gamba is Gallina’s close associate and spokesman, although his father, Count Ruggero Gamba, tries to talk some sense into him.

Gallina refuses to back down, even though no one but Ravenna seems ready for such a risky adventure. The authorities are watching them closely and know that Gallina and Gamba are working with the “English Lord.” Although Bologna seems to be the center of the conspiracy, the secret police observe that in Ravenna “many young men have small cards with the emblem of Liberty hidden in their hats.”

When August comes to an end and the Austrians have not moved, Gallina tells them all to hurry, because at the beginning of September the money from the local tax authorities will be collected in the government offices and it is a good opportunity to grab it before the authorities send it to Rome. On the other hand, the Papal authorities are reluctant to arrest them, fearing that they will not find enough incriminating evidence against them and will have to let them go. In December 1820, the head of the Papal guard is murdered in Ravenna, outside Byron’s house, but this does not deter them. In January 1821, Byron is in charge. He assures Gamba and Gallina that all the liberals can find shield in his house, if necessary. On January 29, while riding his horse in the woods outside the city, Byron encounters a group of armed men singing at the top of their lungs, in the Romagnol dialect, sem tutti soldat per la liberta (“we are all soldiers of liberty”). They stopped when they saw Byron to cheer him on.

Despite Gallina and Byron’s best efforts, the affair ended in a fiasco. They were all arrested and ordered to leave the city by July 1821. Byron was not touched but was shown to be undesirable – he finally left in October. Gallina went to Corfu and from there to Messolonghi, where he met Mavrokordatos, who had just settled there. But those Carbonari who made the mistake of staying in Ravenna, reassured by the initial mild reaction of the authorities, later regretted it. With the arrival of Austrian troops, they were arrested, interrogated exhaustively and finally sentenced to death by Cardinal Rivarola in August 1825 – their sentence was commuted to 25 years imprisonment. Rivarola invited Gallina and the other exiles to return and accept the strict conditions of the amnesty.

But Gallina was already being celebrated in Greece. In the summer of 1822, European newspapers reproduced a text he had written shortly after the end of the National Assembly in Epidaurus. It emphasized not only his role in writing the Constitution, but also his place in the new Greek revolutionary state. As secretary-general of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was in fact Theodoros Negri’s closest associate. In fact, the Greek administration had honored him by including him among those who would receive a special medal for their participation in the National Assembly of Epidaurus, i.e., the “founders” of the modern Greek state!

In the days when the laudatory articles were published in the European newspapers, the Papal authorities arrested his comrades, while Gallina was preparing to visit Athens. But when the news of the Ottoman general Mahmud Dramali Pasha’s march to the Isthmus of Corinth became known, the panic was so general that everything fell apart within a few days. Gallina fled in a miserable condition to the island of Aegina and from there to the island of Syros, from where he soon left Greece for the Crimea, following a Dutch merchant as a clerk.

On April 6, 1823, from the lazaretto of Theodosia in the Crimea, he wrote to Mavrokordatos the details of his adventure. “I wanted to come to Messolonghi to meet you, but I did not have the means.” The last news of Gallina is a letter of recommendation addressed to Mavrokordatos (through Christodoulos Klonaris) for the volunteer Major Lambert from Silesia, in 1824. From there his traces disappear.

I have gathered various information, but it is all uncertain. According to the prevailing view, after Russia he went through Constantinople, was captured by pirates and ended up as secretary to Muhammad Ali, the Pasha of Egypt and father of Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt – long after the end of the Greek Revolution. On a trip to the Middle East, Gallina died in Aleppo in May 1842. But even this is not certain.

In 1848, a Vincenzo Gallina was in Livorno as consul of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and, until 1862, had a continuous correspondence with the protagonists of the Italian struggle for independence, Daniele Manin and Giuseppe la Farina, who seemed to trust him. Is he the same person?

But one question I (and the Austrian investigators) had was, probably, solved. Why was Gallina the instigator of the uprising in Romagna in August 1820? Why did he not consider the risks and act so recklessly? I found a possible answer in the court records of the time. On July 24, 1820 (a few days before his urgent appeals for an immediate uprising), Gallina had lost a lawsuit in the Commercial Court and had to pay various sums to his opponents. Probably desperate because he was bankrupt, he had nothing left to lose.

The author is particularly grateful to Dr. Claudia Ambrosio at the Archivio di Stato di Roma, and to the doctoral candidates Sophia Pilouri (University of Athens) and Margherita Pinzani (Università degli Studi di Messina) for their valuable assistance in his research.

This article was originally published in Greek in the Sunday edition of Greece's largest newspaper, Kathimerini. The text you have just read is a product of my research and presents some of my original findings to a wider audience. Please respect intellectual property rights and ethical norms in research. You can read more (if you can read Greek) here and here. For an excellent book on the revolutions in the Iberian and Italian peninsulas, Sicily, and Greece in the 1820s, see here.