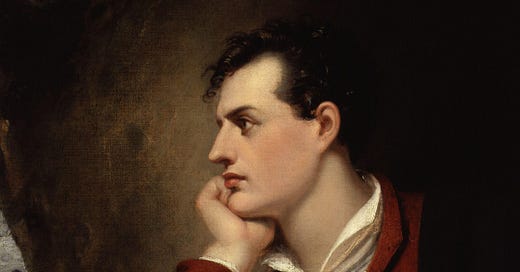

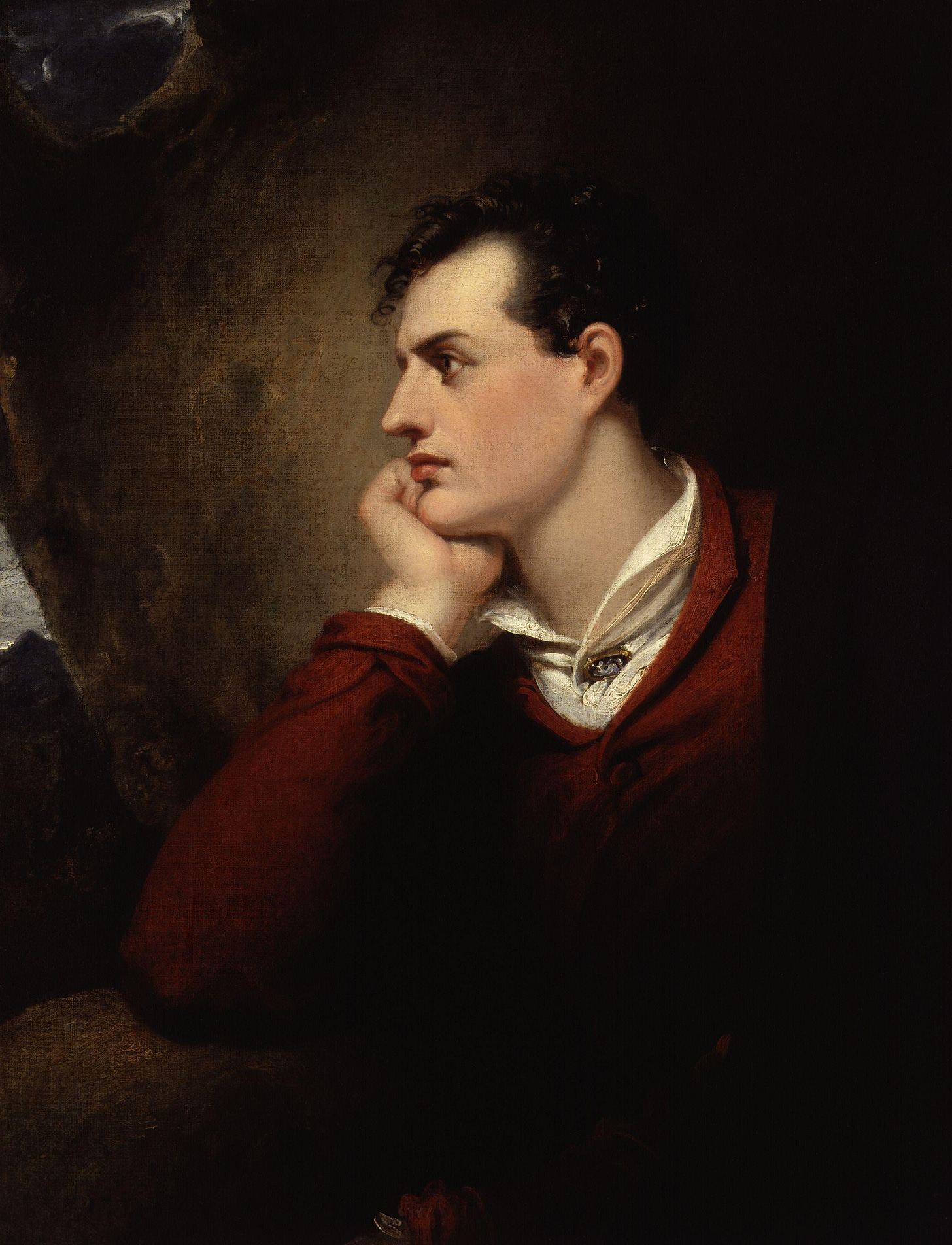

Byron on Liberalism

What kind of liberal Byron was, and what did liberalism mean in the early 1820s?

On January 29, 1821, Lord Byron was riding his horse in the woods outside the town of Ravenna, when he suddenly saw a group of armed men in front of him. These men were singing with all their might a song in the local dialect:

Sem tutti soldat per la liberta.

[“We are all soldiers of freedom”.]

Byron immediately understood that they were all members of a group of Carbonari who called themselves the Americani. They were so called because they frequented a tavern in Ravenna called the Americano. Their leader was a merchant with radical liberal ideas, Vicenzo Gallina. Byron had been introduced to Galina by a mutual friend, the young Count Pietro Gamba, brother of his mistress Teresa Guiccioli. Gamba was of the same mind as Gallina; in fact, he was his second in command. Together they planned an uprising in Ravenna, when the Italian patriots would rise up simultaneously in all the cities of Romagna, especially in Bologna. At least that was the plan.

But it didn't work. The leaders of the Carbonari hesitated. Some had withdrawn, others were afraid. Gallina pushed as hard as he could, but he could not convince the other leaders of the conspiracy. Except one, Byron. The British poet had been initiated into Carbonarism, and although everyone had given up the idea of rebellion, Byron, Gallina, and Gamba continued to plan. The Papal authorities watched them closely, and at one point they intervened. They asked Gallina and Gamba explicitly, and Byron as discreetly as possible, to leave the city and the Papal States immediately. Byron and Gamba ended up in Genoa and then in Greece where they both died, Byron in 1824 and Gamba in 1828 (under unclear circumstances). Gallina was the first to arrive in Missolonghi in the summer of 1821, he met Alexandros Mavrokordatos, the Greek political leader, and collaborated with him in the drafting of the first Greek constitution of 1822. Gallina was honored by the revolutionary state as one of the founders of modern Greece. [for more on Gallina read this]

We return to Byron, and I remind you that he is in the forest and has come upon the group of singing Carbonari. As he passed them on his horse, they cheered in his honor, and he, pleased, waved them off in a friendly manner.

“They cheered me as I passed – I returned their salute, and rode on. This may show the spirit of Italy at present.” he wrote enthusiastically in his diary that evening. It had already been agreed with Gamba that, whatever happened, the liberals of Ravenna would gather at his house.

In his Ravenna diary and letters, we find at least 12 mentions of the word liberal with its political meaning. Byron identifies the Carbonari with the Liberals, he twice mentions the “wild spirit of the Liberals here”, he characterizes the Gallina group, the Americani, as “a liberal group”.

Everyone else seems to label Byron himself as a liberal. He complains, but rather smugly, that “they denounce me as the head of the Liberals”, he writes to Richard Hoppner, the British consul in Venice. A Milanese newspaper, as he wrote to Thomas Moore, “detests me heartily and abuses me on all occasions as a Liberal”. When the Papal authorities decided to dissolve the liberal club in Ravenna, in mid-July 1821, they forced its leaders into exile. Byron was frustrated because “Teresa and her father are obliged to retire, which is most likely, as the whole family are Liberals”. However, the frustrated Terese believed that the real reason that led her family into exile was her relationship with Byron. Byron, for Teresa, is considered by the “anti-liberals” as “il principale sostegno del Liberalismo della Romagna,” i.e. the main supporter of liberalism in the Romagna region.

One finds quite fascinating the fact that Byron uses the words “liberal” and “liberalism” rather liberally and without much thought – considering the fact that the word is still rather unknown in the English language.

I suppose you know that these words, liberals and liberalism, were coined in Spanish and are associated with the supporters of the Spanish Constitution of 1812, the Constitution of Cádiz. The association of Spain with the origins of the concept of liberalism and liberal ideas was not a historical accident. I belong to a minority of scholars who believe that liberalism was born not in Scotland or the British Isles in the late 17th century, but during the 16th and 17th centuries in the School of Salamanca.

But that is another story.

The word “liberalism” as a concept describing a political ideology associated with constitutionalism and individual liberty emerged in Spain after King Ferdinand decided to abolish the Constitution in May 1814. His political opponents were called “liberales”. The word spread quickly. The political opposition to the restored Bourbon monarchy in France was also called the “liberal opposition”; the so-called Independents, with leaders such as the Marquis de Lafayette and Benjamin Constant.

Now be careful!

Constant was a key figure in early liberalism. It was he who dissociated early liberalism from classical republicanism in his famous 1819 speech on the differences between the ancient and the modern (i.e., early 19th century) meaning and content of liberty. I characterize him as the first truly classical liberal intellectual in the modern sense of the word.

But even Constant does not use the terms “liberal” or “liberalism” in his essay. We mistakenly believe that the term was widely used in France during the early Restoration, but this is an effect created by Balzac, who uses the word to characterize the opposition when he writes his novels in the 1830s, i.e., after the liberal July Revolution.

In the early 1820s, the French newspapers used the word in italics, only in connection with Spain, and with a rather disapproving tone. The leading French liberal newspaper, the Constitutionnel, used the word for the first time in January 1821, again in connection with Spanish liberals. In contrast to the conservative newspapers, the newspaper is friendly to “liberalism in opinions” and the “constitutional spirit.”

Now, in the English language, “liberalism” has the same origins. We can find the first mention of the word in the January 29, 1816 issue of the Morning Chronicle. The London newspaper described the persecution of constitutionalists in Madrid, who were accused of “the crime of liberalism” (italics by the newspaper). Three days later, in an editorial, the same paper repeated the word when it described the decree against the Spanish liberals “for the crime which in Spain is emphatically called liberalism” [again, italics by the newspaper]. It took the paper more than three years to use the word again, without the italics. In a letter from a correspondent in Barcelona, we read that in that city “there is a spirit of liberalism that has always been the result of the love that the Catalans have always had for the sacred cause of liberty”.

By 1820, the word was known but used only by intellectuals. In September 1820, Alexandros Mavrokordatos, the moderate liberal who will become the political leader of the Greek Revolution, sent the following order to his bookseller in Geneva:

I am very interested in political pamphlets. You can choose for me on this criterion: I am not a staunch partisan of either party, but I prefer to read the arguments of ultra-liberals than those of ultra-royalists. Please send me as many of the new pamphlets as you can find. I am especially looking for two pamphlets that are making a lot of noise at the moment, one written by Count de Kératry and the other by Benjamin Constant.

From the very beginning, liberalism was identified not only with constitutionalism, but also with free trade and capitalism, and thus with “immorality“. In a letter to the editor, published by The Times (Feb. 12, 1820) we read that “it is to be feared that the new school of commercial liberalism has been deeply revolutionalised by the demoralisation practiced under the Berlin and Milan decrees.”

In a very interesting article published in the May 1820 issue of the Monthly Magazine, a 32-year-old Englishman, Robert Francis Jameson, totally unknown today, writing from Havana, identifies liberalism with capitalism, but also with personal autonomy. The author emphasizes how difficult it is to be a true liberal, because the liberal “philosophy is beautiful in its theories; but come to an application of them, and you begin again.”

He uses a very interesting example to demonstrate the hypocrisy:

“The capitalists of France and Germany, in spite of their liberalism, revolt against their own doctrine; when it is to portion out a daughter or to seek alliance by marriage.”

The same person accuses liberals of being unwilling to accept moral and political equality between whites and blacks.

The hypocritical unwillingness of liberals to apply their principles to anyone other than white, middle- or upper-class gentlemen was (and it still is) an endemic, endogenous problem. 80 years later, in a partisan liberal newspaper published in the English East Midlands, one can read this horrible (even for 1896 standards) anonymous article:

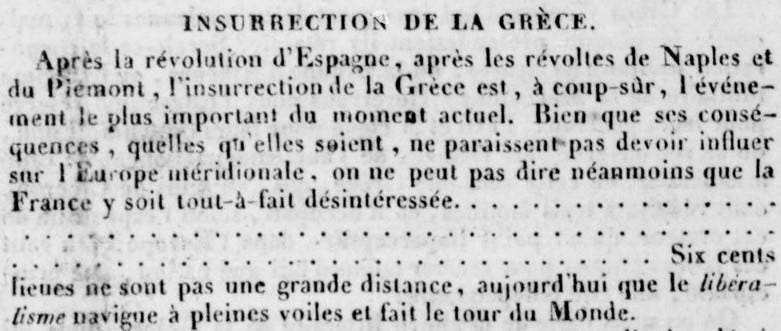

Back to the 1820s. As the revolutionary movement spread in southern Europe in 1820-1821, the conservative press adopted the Metternich conspiracy theory that all revolutionary movements were organized by the “workshops of liberalism,” as the conservative Gazette de France pointed out. It is the same newspaper that, in April 1821, published the most well-informed editorial on the Greek Revolution, characterizing it as a “liberal” revolution. The editorial was written by its editor-in-chief, who attended the Congress of Laibach:

But let's go back to Byron, the head of the liberals in Romagna.

What kind of liberal was Byron?

I think Byron had adopted a version of liberalism that was not so much a coherent ideology as a desire to have one’s heart in the right place, that is, to be more friendly to liberty than the royalists, the conservatives or the Church. He was not as radical as Percy Shelley, not as consistent in his views as Constant or John Bowring (one of the few liberals of the time who was involved in every progressive pro-liberty cause, from women’s rights to the abolition of slavery and from free trade to the public education).

This version of liberalism was described in a comprehensive and timely definition that remains relevant even today (and it has inspired our Substack), written by a 19-year-old girl, Mary Godwin, who became famous as Mary Shelley.

According to Mary, liberals were “all those of every nation in Europe who have a fellow feeling with the oppressed, and who cherish an unconquerable hope that the cause of liberty must at length prevail.”

The relation of Byron with liberalism was accurately described by Walter Scott, in a letter to Thomas More.

On Politics he used sometimes to express a high strain of what is now called Liberalism; but it appeared to me that the pleasure that it afforded him as a vehicle of displaying his wit and satire against individuals in office was at the bottom of his habit of thinking. At heart I would have termed Byron a patrician on principle.

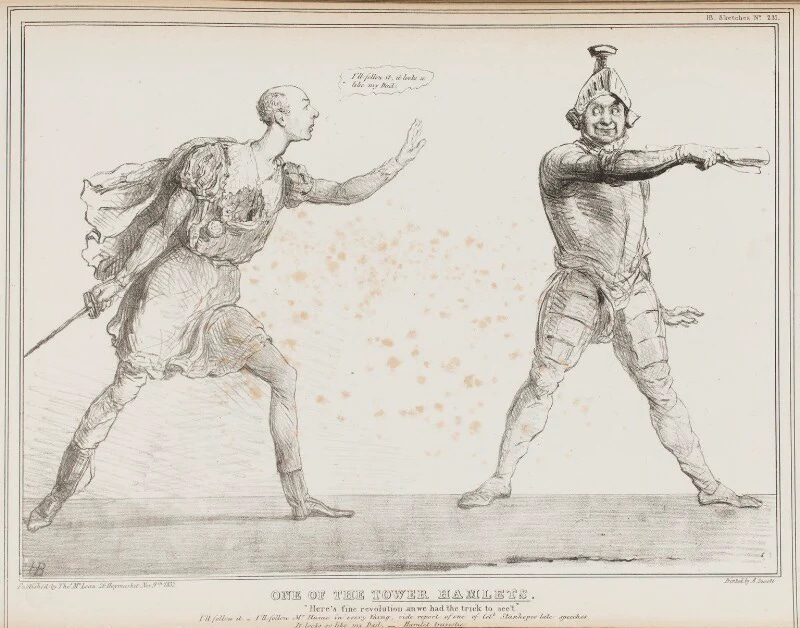

A few weeks before Lord Byron’s death at Missolonghi, the poet engaged in a heated debate with Colonel Leicester Stanhope over control of the Greek Chronicles, the revolutionary newspaper sponsored by the London Greek Committee. The debate also touched on the broader issue of the limits of press freedom during revolution. Stanhope accused Byron of illiberalism, and Byron derided Stanhope’s utilitarian version of liberalism. The concept of liberalism was still evolving in 1824, and the concept of liberalism as a coherent ideology was still being constructed. Byron considered himself a liberal, but his interpretation of the term differed from that of Colonel Stanhope, Edward Blaquiere, John Bowring, Jeremy Bentham, Leigh Hunt, John Cam Hobhouse, Alexandros Mavrokordatos, or Percy Shelley.

Exactly three years after Ravenna, in January 1824, in a dark modest house, in Messolonghi, Byron is a very different man. Not only is he no longer the ardent Carbonaro of Ravenna who was excited by the revolutionary upheaval and drove his friends into conflict, but on the contrary, he is now the target of criticism from liberals who consider him not only a conservative but also a traitor to the ideas he once espoused.

Byron has come to Greece as the head of an expedition organized by the Philhellenic Committee to help the rebellious Greeks. But Byron is not the real representative of the Committee, only the front man. The real leader of the expedition is the commissar sent by the Committee to control Byron and also to implement the real agenda of the London Committee, which is not only the success of the revolution, but above all the transformation of Greece into a liberal institutional experiment. The commissar was Colonel Lester Stanhope, a serving officer in the British army and a scion of one of the wealthiest families in England.

Stanhope is a liberal and a democrat, although he comes from an aristocratic family. He is an ardent follower of Bentham, he sees everything with blinders on, he is idealistic and quite naive at the same time. His agenda is to establish four newspapers in Greece that will be edited by liberals. In this way, Stanhope believes, he will control the ideological processes. He is not wrong, the newspapers will play a crucial role in the terminology of the revolution, shape political views, form groups, and most importantly, ensure the ideological hegemony of the liberals.

For Stanhope, Byron is no longer the enthusiastic liberal revolutionary, but a dangerous opponent to his cause. In their final dramatic confrontation, in the middle-class home they shared, Stanhope will speak harsh words to Byron:

- You have professed liberal principles since your youth, but now, when called upon to act, you have shown yourself to be a Turk! Your conduct is an attempt to suppress the press, and you abuse liberal principles in general.

Byron responds to Stanhope’s criticism with irony. He attacks Bentham and liberal and radical British politicians.

Stanhope, indignant, also ridicules him:

- Have you borrowed your ideas of free men from the Italians?

This conversation and the clash between the two, a clash we know well from many sources and from the letters of the protagonists themselves, in which they denounce each other in the London Greek Committee, gives us some very useful information about at least two things. About the development of Byron’s political thought and also about the versions of early liberalism.

One version, let’s call it roughly patriotic liberalism, has as its main goal national self-determination and is linked to the idea of nationalism. The second, which we will loosely call constitutional liberalism, seeks to strengthen democratic institutions and is associated with the idea of constitutionalism. [For more read this and this.]

Let’s focus on Byron. One thing is certain, Byron is no longer a Byronic hero. He is no longer the enthusiastic friend of the Carbonari. He’s not the romantic revolutionary. He has matured, he has become a pragmatist, he has chosen to play a very specific role, he has decided to sacrifice many things. But having made his decisions, he is very careful and sets priorities. The main priority for him is to make the Greek Revolution a success, and he has to play a leading role in this success. So not only is he indifferent to the political agenda of the Committee and idealistic liberals like Stanhope, he doesn’t even tolerate them.

Byron had already begun to see things differently at Ravenna, when he realized that (as his friend Percy Shelley wrote) there was more revolutionary smoke than revolutionary fire in Italy. In Greece, he sees the only revolution that has solidified because the Greeks have a clear goal, national independence. Despite the frustration caused by the Greeks’ civil strife, he appreciates the distance Mavrokordatos keeps from them and, moreover, is catalytically influenced by him in the way he sees things. For Mavrokordatos, himself a liberal, the priority is the success of the Revolution, and a condition for this is the appeasement of the European courts. What’s the point of turning the Greek revolutionary state into a radical democratic experiment if the revolution fails because of the hostility of the great powers? Byron is now mature enough to accept this pragmatic view of Mavorkordatos, he allies himself with him, and they both set their sights on containing Stanhope.

But Stanhope has managed to set in motion a mechanism that Mavrokordatos and Byron cannot control. On January 1, 1824, the Greek Chronicle, the most important newspaper of the Greek Revolution, is published in Messolonghi - this year we celebrate its anniversary. The Greek Chronicle is a militant liberal newspaper. Stanhope himself chose its director, the Swiss liberal but also democrat, Jacob Mayer. Like Stanhope, Mayer is a fanatical ideologue. Mayer hates Byron and Byron despises Mayer.

Stanhope and Mayer turn the paper into a vehicle for the dissemination of liberal and democratic ideas ("our intention is to Americanize Greece," Stanhope tells Count Kapodistrias in Geneva, several weeks earlier), but at the same time they do something more dangerous and particularly harmful to the Greek cause: they openly attack European monarchs and support or encourage with opinion articles revolts and revolutions in other European countries. Mavrokordatos and Byron do their best to restrain and tame them, but Stanhope and Meyer are in a revolutionary frenzy.

At the end of January, Byron did not hesitate to ask Mavrokordatos to censor the press. “If I were you, I’d do it!” he tells him.

When Stanhope decided to leave Messolonghi on February 21 to establish a second paper there, again with a liberal editor, George Psyllas, who had been involved in a secret pre-revolutionary German liberal student organization that was responsible for at least one political assassination, Byron did everything he could to undermine him. On March 6, he writes the following to the Committee:

The paper circulating in Messolonghi has done much harm. I have tried to persuade both Mavrokordatos and Stanhope that under the present circumstances we must be very careful with the press so as not to cause damage.

Two days later, on March 8, 1824, the Greek Chronicle would not circulate in Messolonghi as usual. Byron himself censored the already printed number 20. He censored it and destroyed almost all copies because Mayer published an editorial in which he essentially urges the Hungarians to rise up against the Austrians. We know the text because at least one copy has survived.

That night in late January at Messolonghi, the night of the conflict, Byron had warned Stanhope.

- If I want to, I’ll crush the press with my little finger!

And he angrily replied to Stanhope’s protests:

- The principles of justice have nothing to do with politics. Your liberal principles are dangerous. They have done harm in Spain, and they will do harm in Greece!

The end of the Greek revolution may have been followed by 16 years of authoritarianism (1828-1843), but when news of the uprising in support of a constitution, on September 3, 1843, reached London, Stanhope and the other members of the Committee celebrated the uprising at an event they organized. They celebrated because Greece would have a constitution again and the press would finally be free.

In one of the speeches given that night, the former leader of the London Greek Committee, John Bowring, exclaimed as the others applauded enthusiastically:

On September 3 the Greek revolution was complete. It is a pity that Lord Byron is not alive to celebrate with us.

When Byron’s name was mentioned, the British liberals stood up and cheered, just as the Italian liberals had done, 23 years earlier, in the woods outside Ravenna.

The text you have just read is a product of my research and presents some of my original findings to a wider audience. Please respect intellectual property rights and ethical norms in research. The text is based on my presentation at the 48th International Byron Conference, Commemorating the Bicentenary of Lord Byron’s Death. If you are interested in the conflict about freedom of the press in a revolutionary time, in 1824 Missolonghi, read a paper of mine, in SSRN or Academia. If you can read Greek, you might also find this paper of interest. For the best book on Byron’s Greek journey, visit this page..